Here's Marcella Pattyn's obituary from The Economist. (HT Anglicans Online.)

I'm especially moved by the idea that "The beguinages had originally been famous for taking the 'spare' or 'surplus' women who crowded into 13th-century cities in search of jobs." We are headed towards this kind of society today, if we're not already there; global poverty is rising, and unemployment among some sectors of the population is very high. Decent jobs are becoming scarcer. The world doesn't seem to care for its "surplus" people much these days, either. And, of course: it's easy to understand why Marcella Pattyn would have been attracted to the Beguines; "But she was blind, or almost so, and no other community would accept her. She wanted to work, too, and was not sure she could in an ordinary convent."

I'm especially moved by the idea that "The beguinages had originally been famous for taking the 'spare' or 'surplus' women who crowded into 13th-century cities in search of jobs." We are headed towards this kind of society today, if we're not already there; global poverty is rising, and unemployment among some sectors of the population is very high. Decent jobs are becoming scarcer. The world doesn't seem to care for its "surplus" people much these days, either. And, of course: it's easy to understand why Marcella Pattyn would have been attracted to the Beguines; "But she was blind, or almost so, and no other community would accept her. She wanted to work, too, and was not sure she could in an ordinary convent."

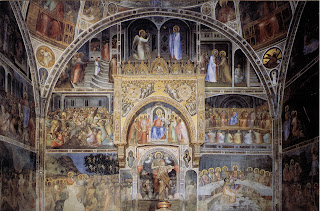

AT THE heart of several cities in Belgium lies an unexpected treasure. A gate in a high brick wall creaks open, to reveal a cluster of small, whitewashed, steep-roofed houses round a church. Cobbled alleyways run between them and tiny lawns, thickly planted with flowers, grow in front of them. The cosiness, the neatness and the quiet suggest a hortus conclusus, a medieval metaphor both for virginal women and the walled garden of paradise.

Any veiled women seen there now, however, processing to Mass or tying up hollyhocks in their dark habits and white wimples, are ghosts. Marcella Pattyn was the last of them, ending a way of life that had endured for 800 years.

These places were not convents, but beguinages, and the women in them were not nuns, but Beguines. In these communities, which sprang up spontaneously in and around the cities of the Low Countries from the early 13th century, women led lives of prayer, chastity and service, but were not bound by vows. They could leave; they made their own rules, without male guidance; they were encouraged to study and read, and they were expected to earn their keep by working, especially in the booming cloth trade. They existed somewhere between the world and the cloister, in a state of autonomy which was highly unusual for medieval women and highly disturbing to medieval men.

Nor, to be honest, was it the first thing Juffrouw Marcella thought of when, as a girl, she realised that her dearest wish was to serve her Lord. But she was blind, or almost so, and no other community would accept her. She wanted to work, too, and was not sure she could in an ordinary convent. The beguinages had originally been famous for taking the “spare” or “surplus” women who crowded into 13th-century cities in search of jobs. Even so, the first community she tried sent her back after a week, unable to find a use for her. (In old age she still wept at the thought of all the rejections, dabbing with a handkerchief at her blue unseeing eyes.) A rich aunt intervened with a donation to keep her there, and from the age of 21 she was a Beguine.

Contentedly, in the beguinage at Ghent from 1941 and at Courtrai from 1960, she spent her days in tasks unaltered from the Middle Ages. She knitted baby clothes and wove at a hand loom, her basket of wool beside her chair, chatting and laughing with the other women. At lunchtime, like the others, she ate her own food from her own cupboard (identified by the feel of the carvings under her hands), neatly stocked with plates, jugs, coffee and jam. Cooking she was spared, ever since on the first occasion she had failed to see the milk boiling over, but she washed up with a will.

A good part of the time she prayed, all the prayers she could remember, but especially her rosary whose bright white beads she could almost see. Most usefully, since she was musical, she played the organ in chapel; and she cheered up the sick, as she nursed them, by serenading them on banjo and accordion. Almost her only concession to modernity was the motorised wheelchair in which she would career around the alleyways at Courtrai in her later years, wrapped in a thick knitted cape against the cold, her white stick dangerously levelled like a lance.

Love’s light

In her energy and willpower she was typical of Beguines of the past. Their writings—in their own vernacular, Flemish or French, rather than men’s Latin—were free-spirited and breathed defiance. “Men try to dissuade me from everything Love bids me do,” wrote Hadewijch of Antwerp:They don’t understand it, and I can’t explain it to them. I must live out what I am.Prous Bonnet saw Christ, the mystical bridegroom of all Beguines, opening his heart to her like rays blazing from a lantern. But a Beguine who was blind could take comfort in knowing, with Marguerite Porète, that Love’s light also lay within her:O deepest spring and fountain sealed, Where the sun is subtly hidden, You send your rays, says Truth, through divine knowledge; We know it through true Wisdom: Her splendour clothes us in light.When she was known to be the last, Juffrouw Marcella became famous. The mayor and aldermen of Courtrai visited her, called her a piece of world heritage, and gave her Beguine-shaped chocolates and champagne, which she downed eagerly. A statue of her, looking uncharacteristically uncertain, was cast in bronze for the beguinage.

The story of the Beguines, she confessed, was very sad, one of swift success and long decline. They had caught the medieval longing for apostolic simplicity, lay involvement and mysticism that also fired St Francis; but the male clergy, unable to control them, attacked them as heretics and burned some alive. With the Protestant Reformation the order almost vanished; with the French revolution their property was lost, and they struggled to recover. In the high Middle Ages a city like Ghent could count its Beguines in thousands. At Courtrai in 1960 Sister Marcella was one of only nine scattered among 40 neat white houses, sleeping in snowy linen in their narrow serge-curtained beds. And then there were none.