Surrexit pastor bonus is the second Matins Responsory for Easter Monday; see it here in its context at Breviary.net. Here is the text and translation from that site:

Unfortunately, there seems to be no plainchant audio recording of this anywhere online. (EDIT: But there may be soon, thanks to Jakub Pavlik (see comments)! Jakub, who lives, I believe, in the Czech Republic, has already transcribed the responsory from the Antiphonarium Sedunense - a 14th-Century manuscript from Domstift Sitten (that's "the Cathedral Chapter" in Sion ("Sitten"), Switzerland) housed at a Swiss manuscript library - and linked to a PDF of the transcription posted at this Czech Liturgy of the Hours website! Amazing.

Here's an image file I created from his PDF; this Responsory was, evidently, put together a bit differently at Domstift Sitten. Notice the second Versicle, which reads "Surrexit dominus de sepulchro qui pro nobis propendit in ligno," which translates as "The Lord is risen from the grave, who for us was hung from the tree."

Many, many thanks to Jakub, who may soon create an audio file of this! Ah, the interwebs....!)

However, many composers have set this text in polyphony - Victoria, di Lassus, Palestrina, L'Héritier, and Mendelssohn, among others. Understandable; it's a beautiful text.

Most have set only the first part of the text; here it is, along with a different (and I think better) English translation:

Here's one recording of di Lassus' version, sung by the Wicker Park [Chicago] Choral Singers:

It would be very worth your while, I think, to click over to this page and listen to L'Héritier's version, sung by the Oxford Camerata; I can't embed it here. Here's what Wikipedia has to say about L'Héritier:

]

And here's an interesting bit about this particular piece:

And wow! How about this terrific take on Mendelssohn's Surrexit pastor bonus, from "Concert de l'Escolania de Montserrat a l'església de Saint-Hilaire de Poitiers - 27 de juny del 2008." Man, these boys can sing!

This sheet-music site offers an interesting anecdote about the Mendelssohn:

Another recording of the Mendelssohn - very beautiful, but in my opinion not as exciting - from the Stuttgart Chamber Choir:

Here's Pieter Brueghel the Younger's "Good Shepherd," which hangs in the Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique. Brueghel lived from 1565 to 1636.

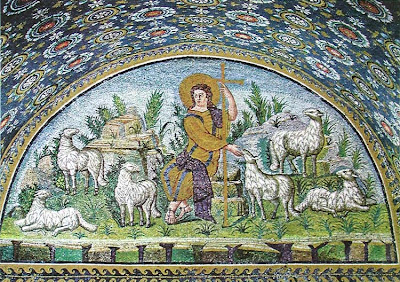

And here's The Good Shepherd mosaic in the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, Ravenna, from the 1st half of 5th century:

R. Surréxit pastor bonus, qui ánimam suam pósuit pro óvibus suis, et pro grege suo mori dignátus est : * Allelúja, allelúja, allelúja. V. Etenim Pascha nostrum immolátus est Christus. R. Allelúja, allelúja, allelúja. V. Glória Patri, et Fílio, et Spirítui Sancto. R. Allelúja, allelúja, allelúja. | R. The Good Shepherd is risen, who laid down his life for his sheep, and vouchsafed to die for his flock : * Alleluia, alleluia, alleluia. V. For even Christ our Passover is sacrificed for us. R. Alleluia, alleluia, alleluia. V. Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Ghost. R. Alleluia, alleluia, alleluia. |

Unfortunately, there seems to be no plainchant audio recording of this anywhere online. (EDIT: But there may be soon, thanks to Jakub Pavlik (see comments)! Jakub, who lives, I believe, in the Czech Republic, has already transcribed the responsory from the Antiphonarium Sedunense - a 14th-Century manuscript from Domstift Sitten (that's "the Cathedral Chapter" in Sion ("Sitten"), Switzerland) housed at a Swiss manuscript library - and linked to a PDF of the transcription posted at this Czech Liturgy of the Hours website! Amazing.

Here's an image file I created from his PDF; this Responsory was, evidently, put together a bit differently at Domstift Sitten. Notice the second Versicle, which reads "Surrexit dominus de sepulchro qui pro nobis propendit in ligno," which translates as "The Lord is risen from the grave, who for us was hung from the tree."

Many, many thanks to Jakub, who may soon create an audio file of this! Ah, the interwebs....!)

However, many composers have set this text in polyphony - Victoria, di Lassus, Palestrina, L'Héritier, and Mendelssohn, among others. Understandable; it's a beautiful text.

Most have set only the first part of the text; here it is, along with a different (and I think better) English translation:

Surrexit pastor bonus,

qui animam suam posuit,

pro ovibus suis et pro grege suo mori

dignatus est. Alleluia.

The good shepherd has risen,

who laid down his life for his sheep,

and deigned to die for his flock. Alleluia.

Here's one recording of di Lassus' version, sung by the Wicker Park [Chicago] Choral Singers:

It would be very worth your while, I think, to click over to this page and listen to L'Héritier's version, sung by the Oxford Camerata; I can't embed it here. Here's what Wikipedia has to say about L'Héritier:

Jean L'Héritier (Lhéritier, Lirithier, Heritier and other spellings also exist) (c. 1480 – after 1551) was a French composer of the Renaissance. He was mainly famous as a composer of motets, and is representative of the generation of composers active in the early to middle 16th century who anticipated the style of Palestrina. He was a native of the diocese of Thérouanne, in the Pas-de-Calais, but little is known about his early years.[EDIT: The video is now embeddable:

According to a note by an Italian contemporary, L'Héritier was a pupil of Josquin des Prez, a relationship which most likely occurred while Josquin was at the French royal court in the years after 1500 (exact years for Josquin's stay there have not been established).

]

And here's an interesting bit about this particular piece:

The manuscript containing Surrexit pastor bonus was a working choirbook for the choir of the Julian Chapel in the Vatican, and is a major source for motets by composers of the post-Josquin generation. It is dated 1536 and bears the coat of arms of Pope Paul III (1534-49). It contains seven motets by Lhéritier, one fewer than the best represented composer, Claudin de Sermisy. It also contains motets by Josquin, Festa, Maistre Jan, Jachet of Mantua, Verdelot, Gombert, Willaert, Lupi, Morales and da Silva.

That Lhéritier's music was highly regarded in the sixteenth century is evident from the number and geographical diversity of sources in which his music is found. Much of his work was published by printers in Paris, Lyon, Rome, Ferrara and Venice as well as in Nuremberg, Louvain and Seville. Moreover, his works were being reprinted well into the 1580s, and manuscripts of his works were compiled as far afield as Spain, Germany, Austria, Poland and Bohemia as well as in France, the Netherlands and Italy. Palestrina based two masses on motets by Lhéritier, and it is obvious that Lhéritier was important in developing the style of continuous imitation from Josquin and disseminating this style in Italy.

And wow! How about this terrific take on Mendelssohn's Surrexit pastor bonus, from "Concert de l'Escolania de Montserrat a l'església de Saint-Hilaire de Poitiers - 27 de juny del 2008." Man, these boys can sing!

This sheet-music site offers an interesting anecdote about the Mendelssohn:

Inspiration for the Three Motets op. 39 was a visit to the romanesque church of Trinità dei Monti. On 20 Dec 1830 Mendelssohn wrote to his parents: "The French nuns sing there, and it is wonderfully lovely. ... Now, one should know one more thing: that one is not allowed to see the singers. Therefore I have come to an unusual decision: I will compose something for their voices, which I rememer exactly..."

Another recording of the Mendelssohn - very beautiful, but in my opinion not as exciting - from the Stuttgart Chamber Choir:

Here's Pieter Brueghel the Younger's "Good Shepherd," which hangs in the Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique. Brueghel lived from 1565 to 1636.

And here's The Good Shepherd mosaic in the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, Ravenna, from the 1st half of 5th century: